Guchi Unveils Empowering New Single “Your Type” Ahead of Forthcoming EP “No Skips, Just Feelings”

8 hours ago

Dark Mode

Turn on the Lights

Our countdown of the Artists of each year of the past decade.

The 2000s ended quite abruptly with changes afoot all over the world. As the naughties drew to a close, pessimists and optimists alike looked forward to a new decade with differing projections but palpable excitement nonetheless. Visibly, the drumrolls of revolution were beating across industries as we welcomed the 2010 and the coming years would irreversibly transform the world before our very eyes in terms of what is possible and how objectives can be achieved.

Nigeria’s blossoming music industry would not be left out. New frontiers would be erected, sonic tentpoles would be sunken into exotic corners of the earth and a new word would be minted to serve as a descriptor for music from the continent; but the musicians remained central. As the decade comes to an end, we take a look from 2010 to 2019 at the musicians who defined the sound and heartbeat of each year.

The post will be updated twice daily over the next couple of days.

2010

Africa Rapper #1

On his 2005 hit song, Baraje, Ruggedman starts out saying “…for those that say I don’t have a dance track…”, painting a picture of the Nigerian hip-hop scene at the time – rich lyricism and socially conscious music but hardly any club jams. Enter Jude Abaga. Where established rappers had a handful of party bops across multiple projects, M.I made a point to deliver his punny punchlines over traditional Afropop beats that were crafted to hit.

The end of the previous decade marked an important moment for Nigerian rap. After years of domination by lyrical poet, Mode 9, Nigerian rap needed simplicity as a step-down from its complexity. Repatriates like M.I. Abaga and Naeto C were able to provide this and found their offerings receiving acclaim. While Naeto essentially left at his peak to further his studies, M.I stayed on and dug deep. By the time of the release of his sophomore album in 2010, Mr. Incredible had made a name for himself as one of the hottest rappers in the country. Before Burna Boy spoke his Grammy nomination to existence on the lead track of his African Giant album, M.I tapped into the prophetic on the much-celebrated Undisputed and accurately predicted his domination of African rap.

Where his first album was an impressive point of call showcasing the range of his talent, the movie-themed sophomore album expanded M.I’s scope, presenting him as a full-blooded creative and shattered the liminalities of being a Nigerian rapper; a trend which others, most prominently Falz, have taken on.

The album was met with popular and critical acclaim alike, leading to multiple nominations including the much-coveted BET Awards Best International Act, and winning him several awards like The Future Awards Musician of the Year and The Headies Best Rap Album. True to the hip-hop game, there is no success without haters, no rap career without attendant diss tracks. Feuding with Kelly Hansome, and lesser-known rapper, Iceberg Slim, M.I released Beef, the third single off MI2: The Movie in the last days of 2010. He ended the year on a high, having decimated his rivals and entered the new year, and decade, as the hottest Nigerian rapper.

Somto Uyanna

2011

The Superstar

If you listen to Wizkid’s delivery on MI’s Fast Money, Fast Cars, there’s ample proof of all that he’ll end up doing in the coming years; his distinct spry voice was honey-sweet and his singing was peppered with pristine inflections and pauses that bore the mark of a potential virtuoso. Except, bar a number of music insiders who knew who the singer, nobody was listening. Or when they listened, they came to hear Mr. Incredible toy with words.

The release of Holla at your Boy in 2010 changed all that. He became a nation’s heartthrob, the crush of numerous girls across a continent and the first genuine Nigerian pop break-out star of a new decade. Capable of switching up the flow, he followed up Holla at your Boy with the sultry Tease Me/Bad Guys that sealed his one-to-watch-out-for status; and began to prepare for what was shaping up to be one of the most anticipated albums in Nigerian contemporary music history.

When Wizkid’s debut album, Superstar, on the Banky W-led Empire Mates Entertainment (EME) label dropped in 2011, it lifted Wizkid from national and continental sensation to veritable cultural figure. Offering a wide range of musical styles, from the emo-tinged Oluwa Lo Ni to the Emeka Ike-style love song, Love My Baby, Wizkid established himself as the monster of love that we have all come to enjoy. But, the most successful song on the album was Pakurumo, a modernist take on Fuji music that still incorporated the party-starting, praise-singing qualities of the ancient genre and became one of the hottest songs in Nigeria in that year.

Like any true popstar, Wizkid’s influence moved beyond the airwaves, with his 2011 signature style of basketball hats, colored skinny jeans and tight-fitting shirts that hugged his small frame becoming popular street style across the nation as young men sought to mirror his fashion style. Just as the young artist was enjoying the start of a great career, celebrity struck. News came that 21-year-old Wizkid had fathered a baby boy. This would be the first of multiple controversies around the artist’s personal life. At the time, Wizkid vehemently denied having a child, painting the reported baby mama as a liar and gold-digger. It would take two years for the artiste to post a picture of his son on Instagram, belatedly confirming that he had become a father.

He would win in the Next Rated category at the 2011 Headies Awards as he closed out a memorable year with the prestigious gold plaque that his gift and year deserved. In that moment, it is unlikely Wizkid, or anyone, foresaw the heights he would yet attain but it was a long way from 2008 when few could recognize him. By 2011, they were all talking about him. He was the most popular young musician in the country by a mile and had ascended to the top of Nigerian music’s Mount Olympus.

Somto Uyanna

2012

Get familiar, Omo Baba Olowo is coming through

In 2012, the Nigerian music industry was in a state of flux. The Don Jazzy and D’banj axis was coming under strain due to the latter’s commitments with Kanye West’s GOOD Music and by March, Mo’Hits Records would cease to exist. Newer stars were needed to fill the void. Step forward Davido. He had released his self-produced debut, Back When, featuring Naeto C in 2011 to accusations of pretentiousness.

Not to be perturbed, Davido returned with a hotter song – released late in 2011 – that lasered its way to the top of charts early in 2012; the Clarence Peters-directed music video for Dami Duro was a blueprint for everything you needed to know about Davido: he was young, self-indulgent, had a solid squad, and wasn’t afraid to spend his money to achieve his objectives. Almost as though something had snapped, he was not content to reminisce about the days when he didn’t have so much, he fully switched to omo baba olowo.

As 2012 went on, OBO started rolling out songs that were backed by an effective promotional campaign that ensured his music was always playing. The trick was to make sure that the audience could not escape his songs. Online and offline, via radio or TV, Davido was muttering words that would find a way to wedge into your consciousness and take up permanent residency there. Every song release, from Ekuro to Overseas got a theatric run that documented life from the point of Davido and his posse.

Davido was larger than life it seemed, moving around Lagos surrounded by a phalanx of friends, family, guards and fans as he truly revolutionized celebrity in these parts by focusing on the artistic and showbiz part of the trade with equal zest. When his debut album, Omo Baba Olowo, dropped, it was celebrated with a lavish party that had Nigeria’s richest man in attendance. The project itself was led by All of You where he laid down the gauntlet to challenge for the throne of popular Nigerian music.

Alien to the Davido and friends theme that had brought him to the top of the music food chain, this was him, alone, staking a claim and stylishly letting the stars of the day, 2face, D’banj, and P Square, know that he was next up. “All my fans make me bigger than/ Because of them I’m bigger than some of you/ Actually, I’m bigger than all of you,” he sings on the track that was interpreted to be a warning for older stars and a call out to musicians of his generation including occasional friend and foe, Wizkid. He needn’t have worried; by the sheer power of his vibrancy, the impact and emotiveness of his music, Davido had ensured that he was the standout performer in a transitory year for Nigerian music.

Wale Oloworekende

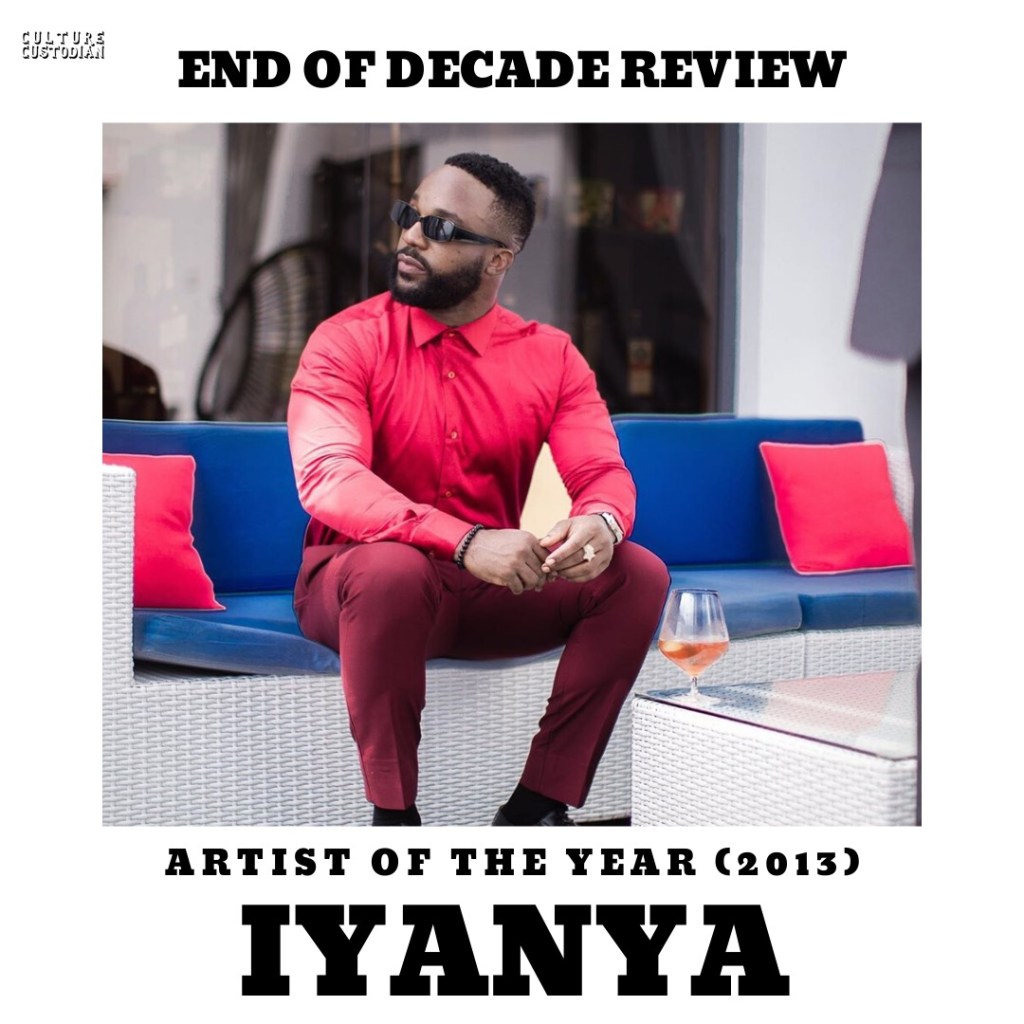

2013

The Blast From The South

The first time I caught wind of Iyanya was not when Kukere dropped like an anvil and earned the ubiquity of pure water sachets. It was much earlier when he won Project Fame in 2008. He looked like a piano bar singer, didn’t he? Always suited and wholesome, often wearing sunglasses. No doubt could sing, but since when has that ever led to mainstream success in Nigeria? What does it matter if you can sing where Nigerians tend to only like RnB-flavoured pop from the lips of American singers?

But try he did.

Iyanya typifies the push-and-pull many Nigerian artists face between what might be your artistic leanings and the realpolitik of giving people what they seem to want. With My Story barely making a dent, he obviously decided that he would not try to be that suited and wholesome guy we first met in 2008. This makes sense. Being popular in Nigeria is a balancing act of approachability and aspiration. Pastors walk hallowed ground but use down-home examples that make sense to you. Politicians cruise around in long envoys with SUVs and Hilux trucks but stop by roadsides for roasted corn around election day. Likewise, Nigerian artists may well have immense vocal range, but their success lies in their ability to craft songs that everyone else can sing. Anything that requires too much vocal dexterity will earn plenty of loud applause live but is unlikely to have much appeal beyond that. And what’s the point in that? Iyanya needed to win, but not necessarily on his own terms.

Kukere was a shedding of skin, literally. The button shirt and suit gave way to a singlet and tight jeans, showing off his tattoo and muscular arms. That voice was gone, too. It took me a minute to even link him with the guy who won Project Fame in 2008. This was a completely new person. Kukere was released in December 2011 and was number one on pretty much every chart from Soundcity and MTVBase, as well as on constant rotation on every radio station. Already a monster of a song, D’Banj jumped on the remix in August 2012 and made the song even bigger and extended its shelflife. No wonder Iyanya won the Song of the Year and the Best Pop Single Awards at the 2012 Headies. It was still getting plaudits a year later, winning the City People Entertainment and Nigerian Entertainment Awards in 2013.

What followed Kukere was a strong run of hit singles that cemented his ladies’ man reputation. Other hits from the Desire album with Kukere were Jombolo featuring Flavour, Sexy Mama, and Ur Waist with Emma Nyra released in 2012, the last of which also earned him more nominations at The Headies in 2013. It was also in 2013 that he headlined a concert in London, UK, and did a mini-tour in the US while racking up endorsements locally with Zinox Computer and Solo mobile phones.

But things were far from rosy for Iyanya. Amidst the whirlwind of success, Iyanya would soon learn the fragility of his position at Made Men Music Group (MMG). In an interview with Joey Akan for Native Magazine, he tells of how on a day in 2012 or 2013 he got a call from a strange number intimating him about the fragility of his position as a partner of Made Men Music Group (MMMG). Following up, he learned that his name was indeed not included among the bosses of the music label he was part of and which he had been helping to run.

Iyanya is not the first artist to taste success amidst grim issues with a label, but it does point to something about how shaky the business relationships that support the industry are. From issues with piracy to the fluidity of ownership structures and lack of legal cover for everything from royalties to contracts, there is plenty of room for exploitation, and it drives a lot of artists to set up their own labels to mitigate these risks. In music, as with everything else in Nigeria exploitation is a feature, not a bug.

This breach of trust ruined his relationship with Ubi Franklin and had him looking over his shoulder until he finally left the label. He joined Don Jazzy’s Mavin Records in October 2016 but that, too, was shortlived. At last check, he was with Temple Records.The industry is about riding the wave as long as you can, getting off, and getting back on again if you can. Iyanya is still making music, and he might even have another song that does quite well one day. It will come at the expense of some reinvention, but that is not impossible. We already know that he has done that before already, and won.

Saratu Abiola

2014

Wizkid: From Ojuelegba, delivered to the world

By the beginning of 2014, it was clear that Wizkid would be leaving Empire Mates Entertainment (EME). He had joined the record label in 2009 as a 19-year-old outsider looking in and five years later he was the man, at the centre of the ebbs and flow of Nigerian music and pop culture. In his stint with the label, he released his highly successful debut album, Superstar, contributed to the well-received EME compilation album and become one of the biggest Nigerian artistes. It was time to bid farewell.

Wizkid had floated his record label, Starboy Entertainment, and was ready for the next part of his career. In 2013, he dropped a song, Caro, featuring L.A.X that was a clear signal of his expansionist aspirations. There was, however, the small detail of a last album with EME. He duly obliged, as early in 2014 rumours began to swirl that his sophomore album was finally in the works. As the months passed and tracks rolled in, it became clear that Wizkid was reaching for goosebumps and memories in his music with the love-themed On Top Your Matter and the nostalgic Show You the Money – the video filmed in his old hood – to show for his efforts.

This was the peak of sappy lyricism on the Nigerian soundscape and Wizzy was at the forefront of inventive songwriting in this regard, mixing catchy phrases with unexpected ranges of singing like only he can. Joy was a departure from the typical Wizkid theme of money, women, and cars as he shone light on maternal love and sacrifice while the Phyno-assisted Bombay was a return to the familiar. He had the hit singles, the looks, insane amount of radio plays, and as much output as any artiste out there. The moment was perfectly aligning sonically and commercially for an album.

Ayo, the sophomore album named after Wizkid, was released on September 17, 2014, and received mostly mixed reviews from critics for the monotony of the album and the lack of maturity of some of the lyrics but nonetheless it was a commercial success sealing Wizkid’s position as the biggest Nigerian star at that moment. On the project, he was everything: lover, mummy’s boy, debauchee, and human. Ayo lacked the raw and dazzling quality of Superstar but that summer was when Wizkid’s star power and cultural weight were decisively confirmed for doubters. He was big; too big in fact to fail and naysayers were going to have to deal with it.

More consequentially, Ayo housed the gem that would come to be regarded as one of the biggest Nigerian songs of the last decade and singularly position Wizkid as the de-facto face of the ‘Nigeria to the World’ movement for a number of years. Ojuelegba was an aspirational anthem made to – once again – give listeners a glimpse into where he grew up from and how he navigated life as a young lad in Surulere. The immaculate production of Legendury Beatz and the moving hook of the song ensured that Ojuelegba moved beyond the constraints of time and space into several ears across the globe powered by the Internet’s unending reach. At the end of the year, Rolling Stone would name Ayo on its 15 great albums you didn’t hear in 2014 list and it would be the start of an intense international fixation with Wizkid. Months later, a remix of Ojuelegba surfaced that had British-Nigerian rapper, Skepta, and Canadian behemoth, Drake, on it. And the rest is, literally, history.

By 2014, the Nigerian music industry was diversifying, pulling diverse influences from sounds on the fringes, but the Wizkid formula remained. Starboy was the monster of hits churning out club bangers with a freakish consistency while making lovers’ anthems on the side, some of the stuff he released was so sensational that it makes some listeners consider 2014 his last truly great year. All things considered, that was the year that sealed his legend and crowned him a king among other kings.

Wale Oloworekende

2015

Eyan Mayweather

After one of the hottest runs ever in Nigerian music, 2015 was the year that Bariga-born emcee turn vibes connoisseur, Olamide, put his feet down and crowned himself the best in the game. Long hailed for his dogged adherence to a syncretic crop of rap that had Yoruba at his core, Olamide had been on a steady – and later meteoric – rise since his 2011 debut, Rapsodi, announced him to a public that was beginning to fall in tune with indigenous rap. In a post-Dagrin world, Olamide had, first, risen to the position of premier indigenous spitter in the land and then, with finesse, the biggest Nigerian rapper, full stop.

2015 was not a year for a lot of rapping from Badoo though as he hunkered down on his other strengths more than ever. The greatest weapon that Olamide has always possessed is not his ability to fuse weighty words together for a grainy rap verse or deliver a flawless amalgamation of conscientious lyrics that appeal to your sensibility; his superpower has always been his ability to re-invent and stay ahead of the herd while renewing the waters of Nigerian pop culture with slangs, buzzwords, and music that formed the soundtrack to life as we knew and appreciated it.

With Wizkid and Davido focused on their ‘Nigeria to the World’ campaign, Olamide held the fort and ruled the realm in every sense of it, kicking off 2015 with a guest appearance on Reminisce’s Local Rappers alongside regular collaborator, Phyno. The effort of the trio who rapped predominantly in their local dialects was interpreted, by some, as a shot at Nigerian rappers who plied their trade in English but to others, it was just a creative affirmation of the central status of indigenous rap in Nigeria at that time. Three months later, Olamide and Phyno released a joint album, 2 Kings, that was critically acclaimed despite the perception of it being stylistically safe – an element of rawness and uninhibition that is at the core of a majority of Olamide hit records was not present despite the profound vulgarity – and popularity – of Ladi featuring Lil Kesh.

Bobo changed that. Released weeks after 2 Kings, Bobo was the quintessential Olamide hit single of the mid-2010s that had slangs appealing to the high and low of the community (think Naira Marley before Naira Marley). A key part of the song’s success was its ability to produce an organic dance routine that went viral, something previous Olamide songs had not quite been able to achieve in the past. The success of Bobo and the staying power of Olamide ensured that his shadow was able to loom over Nigerian music as he helped protégé, Lil Kesh, perfect his breakthrough while being, himself, at the top of charts.

Then came the swivel to regretful lover on Melo Melo that showed depth to his art as well as a genuine lover anthem from a street-pop artiste. In a year of continuing firsts, Olamide also crafted another first: making a song that was exclusively for and from Lagos. Lagos Boys was not the biggest song of the year but it distinctly showed a lurch from top rapper to pop star/cultural icon that was gratifying for Olamide as well as the community that he came from.

By October the signs were ominous. Like he had done every year in the early 2010s, Olamide seemed primed to release another album to bookend what had been another successful year for him and his expanding record label. Eyan Mayweather was released on November 23, 2015, and was led by the inflamed titular track that announced himself as the best rapper doing it with the receipts to back his claim. And nobody could dispute it.

Olamide is not so much the poet laureate as he is the chief hedonist of a generation and 2015 was the peak of his special breed of pleasure-seeking with a mixture of sybaritism and his only request was this: that you danced. And everywhere you went in Nigeria, they were dancing to his music, pulling off different variations of the viral shakiti bobo dance in loving homage to the master.

Wale Oloworekende

Tekno

The Year Of The Slow Down

2016 was memorable for a visible slowing down of the pace of Nigerian songs. The year marked a sharp caesura on the spirited and exuberant sounding influences that had become a staple within the music scene all through the decade. Songs suddenly swerved from having drum-heavy loops to being built on dreamy lo-fi meshes that were crafted to accentuate the voice of the artistes.

At the center of this ripening movement was Made Men Music Group musician, Tekno, who entered the year in a position of strength. In Nigeria’s singles-focused market, his 2015 mid-tempo song, Duro, had cracked the mainstream, introduced his penchant for playful lyrics that were in the strictest sense only melody-inclined, and established him as one to look out for in 2016; after some starts and stops, Tekno was finally on the road to fulfilling the expectation on his talent that had been building up since Holiday.

It was a position he clearly reveled in. Waiting till after the middle of 2016 before he released his first single of the year, Tekno returned with a perfectly cooked up song over – what was becoming – a signature minimalist beat that was another addition to his catalog of love songs. Riddled with indiscernible lyrics, superb production by Krizbeatz, and the star quality that was marking Tekno out, Pana was fated to find its way to up on relevant charts in Nigeria and beyond. And it did with unassuming grace, toppling anything that stood in its path. In August, one month after the song dropped, the official video for Pana was released. Increasingly, it was becoming clear that this version of Tekno was suited, booted and ready for business.

Word soon began to fly that an album was in the offing and Tekno played to the gallery when another song, Diana, came out in October. Diana, unfortunately so, was lost in the acclaim and attention that Pana had gotten, being relegated to the background, not for any fault of its but the sheer staying power of its predecessor in enduring iconography of Tekno’s weight in summer 16 as he fought off fierce competition from Mr Eazi to run the rule over 2016.

Unfortunately, that Tekno album never saw the light of day. Further getting his head into the clouds, he showed arrogance when criticising his inclusion in the Next Rated category of the Headies award in 2016 despite never having released a body of work – one of the key criteria for the category. He was ultimately disqualified but even that couldn’t dampen what had been a memorable year for the singer. Not easing up, he returned with the quasi-protest anthem, Rara, to see out 2016 in a haze of glory.

Most of the songs released by Tekno in 2016 were whimsy but they hit a sweet spot between enjoyment and evolution of our pop sound. If the burden of a nation’s gaze was weighing heavily on Tekno in 2015, he didn’t show it as the preceding year marked the moment when he broke through, fully becoming one of afropop’s biggest stars, getting mentioned in the same breath as the big two if only for a fleeting moment.

Wale Oloworekende

2017

The Year of Mr. Ronaldo

2016 was a bad year for Davido. In the time since releasing his debut album, 2012’s enjoyable Omo Baba Olowo, he’d found himself summoned to the high table of Nigerian music and consequently become one of the artists who most defined his generation. The break up of Mo’Hits and the collateral damage it had on Wande Coal and D’banj’s careers essentially opened up the doors for a new generation of artists like OBO, his frenemy, Wizkid, and others like Burna Boy, Tekno and Kizz Daniel who were able to center themselves in the cultural landscape.

This was a time where the telcos – through eight figures endorsement deals and the success of an offering like caller tunes – were the most prominent financiers of Nigerian music. As the era of #NigeriaToTheWorld was approaching, Davido found himself leading on one front. Sony Music, looking for assets on the continent, signed OBO to a record deal in the first of what would become a rite of passage for the country’s biggest stars. Making the classic mistake of forgetting who the artist was, the label and the artist sought a different direction and ended up with eggs on their faces. 2016’s Son of Mercy was a musical misstep. Gbagbe Oshi, a poor attempt at patois-influenced music, fell flat while the Tinashe collab, How Long, sounded exactly like what it was: a music label focus group that went wrong. The EP did more harm than good for Davido as his domination on the home scene was genuinely in doubt and it failed to resonate with the foreign audience which was being courted.

Davido would go on to describe the album as “wack” and that period would, ultimately, prompt a shakeup. Out went manager, Kamal Ajiboye. Back came Asa Asika. Out went #NigeriaToTheWorld, in came #BackToBasics. Davido’s 2017 might be the greatest year of domination in Nigerian contemporary music. Smarting from 2016’s failure, the artist moved back to Nigeria seeking a new sense of direction and purpose. Tekno, who’d set himself apart as an upper-tier producer and artiste in the preceding year pitched a record he thought was a perfect fit. Davido, on the other hand, took no proactive steps to hear it and thus a state of limbo emerged. To hear Davido tell the story as he did at a listening party for his latest album, A Good Time; on one of those famous Lagos nights at Quilox as the weight of the artistic disconnect fell on his shoulders, Tekno showed up and from a distance gestured that they go to the studio and do what they’d been procrastinating. The duo went to the studio and cut If, the song which would reboot Davido’s career.

Fall followed and a year of total domination ensued. Essentially, as the speed of afrobeats slowed down thanks to the efforts of the likes of Julz, Mr. Eazi, and Tekno, Davido reinvented himself and found himself, once more, at the forefront. As the last quarter of the year wound down, two incidents threatened to derail the progress made. First, was the unfortunate passing of Davido’s associate, Tagbo, after a night of heavy drinking which the authorities maliciously tried to pin on the pop star. Next was the death of a friend and musical associate, DJ Olu. As the force of adversity pressed heavy on him, a studio visit at the peak of the controversy resulted in Fia, possibly the greatest single in his canon. The second verse of the single took aim at actress Caroline Danjuma and the Commissioner of Police, who armed with a desire to scapegoat took to live TV and irresponsibly announced his address, while the rest of the song captured some of his insecurities.

The organic success of If and Fall in the U.S after the failure of Son of Mercy, validated the back to basics approach and those instincts that outsourcing his creativity to label executives would not prove beneficial. The haste with which Fia was put together detracted from the greatness of the final single, Like Dat, but it did confirm 2017 as the year where Davido, Mr. Ronaldo, hit his shots and solidified his legacy as one of his generation’s greatest.

Oluwamayowa Idowu

2018

The Year of Ye

In December 2017, Burna Boy was in a bad place. His headline concert scheduled for the 17th was canceled by promoters, Bavent Street Live. In a statement announcing the cancellation, it said, “this is solely due to the recent allegations leveled against Burna Boy, which are as of now unfounded and are yet to be proven. Burna Boy and his management are working assiduously within the ambits and requirements of the law to clear his name in these investigations.” At the time, the artist christened Damini Ogulu was dealing with a legal case. As the rest of the industry oscillated around Davido in the wake of his monster year, Burna was on the outside looking in. Like all true greats, that period of adversity moved a needle within the artist. It was time to cut out the streak of self-destruction and remind people of his status as the original rockstar of Nigerian music.

In the right context, the events of 2017 were essentially the foundation for 2018. In June 2016, Burna arrived in London to fans waiting for him at the airport, an indication of the high esteem with which he was held. That trip was symbolic as it marked his first time in the UK in five years and his overcoming of an immigration snafu. It also ensured Burna was now more accessible to what would be one of the key audiences in his goal for world domination. Drake’s More Life released in March 2017 famously had Burna’s vocals in the background – another indication of the high esteem in which he was held. A record deal with Atlantic Records via its Bad Habit imprint was also in the works and thus, Burna spent a larger part of the year recording what would prove to be the catapult, 2018’s Outside.

In a different world, Outside would probably have been a mixtape. It was designed to serve as an introduction to the artist that was Burna Boy for an audience that might not have been fully aware of who he was. The project played to his strengths as an afro-fusion artist with the ability to channel a buffet of genres and pepper it with his signature style. With features limited to Mabel, Lily Allen, and J Hus, it was important that Burna’s sound wasn’t lost and that the features amplified him which they did. Outside also landed at #3 spot on the Billboard Reggae Album Chart – an indicator of what was to come.

Ye was the song that essentially catapulted Burna into what we now refer to as the Big Three – the holy trinity of the country’s biggest acts i.e Wizkid, Davido and Burna. What has since been referred to as the unofficial national anthem – Ye -was Burna at his finest, using melody and simple lyrics to reflect the feelings of the typical Nigerian experience. Soke and Pree Me were songs from his discography which had covered similar themes but essentially came before their time. Proving that its success was essentially destined, certain intangibles worked in its favor. Kanye West’s Ye unwittingly bolstered Burna Boy’s streams and gave us that unforgettable moment of Bankulli screaming “Burna Boy, call me” while recording in Uganda with West. The stars aligned with the success of singles released in the latter half of the year like Gbona, On The Low and Killin Dem. These records were a product of his synergy with Producer, Kel P.

As Detty December wound down, the change in fortunes was clear. Burna Boy had won the hearts of Nigerians again by doubling down on what made him great in the first place: the music. The authenticity and genre-straddling of the project positioned Burna as the best of his class. And boy, did he prove it.

Oluwamayowa Idowu

2019

All hail the African Giant

They say that lightning does not strike twice in the same place. Try telling that to Burna Boy. If there was ever a man born to perfect a follow up to the stunning success that Burna Boy enjoyed in 2018, it would be the singer himself. He had entered the previous year in a curious position: widely heralded as a unique talent but bogged down by a myriad of controversies. But at the end of 2018, he had a generational song and was the biggest musician in the country and, crucially, that position was his to lose. By talent alone, he was more than capable of moving unto greater heights, so a nation watched on.

2019 began with buzz as his collaboration with Zlatan, Killin Dem, began to blow up after its release in December 2018. The song, crafted to the popular infectious Zanku theme, raced to the top of charts and became a certified party starter all over Nigeria. Then the Coachella outburst happened. “I don’t appreciate the way my name is written so small on your bill,” Burna Boy wrote on Instagram about the way his name was announced on Coachella’s poster. “I am an AFRICAN GIANT and will not be reduced to whatever that tiny writing means. Fix things quick please.”

The usefulness of his rant was debated far and wide but it added an expression to the pop culture lexicon. Big font energy became a buzzword across social media and by the time Dangote was released in March, his lead had started to feel like a procession. Everything was clicking, his choices seemed inspired and his music was going all over the world. In March, he collaborated with American production duo, DJDS, on a surprise four-song EP, Steel and Copper.

Steel and Copper was a pleasant auditory experience but there was a grey hue to it that made the project feel incomplete, as though Burna was saving a percipient part of himself for a long-haul marathon that would require gargantuan effort to finish. Nonetheless, he toured extensively, played his set at Coachella while still making his success feel communal; for the public, watching a gifted artiste receive the acclaim his talent demanded was a fitting reward.

News began to come that an album was being made and expected to come out in the third quarter of the year. Released in July, African Giant is a herculean afro-fusion project that blended hip-hop, highlife, ragga, dancehall and afrobeat influences without being obnoxious and monotonous. When the tour de force that the project is fully unloaded, the stunning range of Burna Boy’s talent strikes you. Here is a creator truly comfortable making music and capable of surprising you at any angle. The surprise not being his musical abilities but newer and more reflective takeaways like the soul in his voice on a certain single, the cadence of another track, and how he neatly juxtaposes history and present realities not as random mundanities but results of a long imperfect system that needs everyone’s involvement to fix while delivering memorable music. Burna Boy was taking a message made in Nigeria, identifiable by Africa’s plight in the international system and positioning it for the whole world to see, making sure that the West could not avert their gaze on what is sure to be one of the most culturally significant albums of our times.

Burna’s Grammy nomination in the Best World Music category was the icing on the cake in a year where he has worn many caps. It was ironic that news of the nomination came on the day when the ‘Africa Unite’ concert he was scheduled to headline in South Africa got canceled. No one individual has dominated Nigerian music at a stretch in the manner that Burna has circa 2018/2019 since the heady days of the early 2010s, few have the talent and natural aptitude to anyway. If 2018 was the year when Burna Boy blocked out the distractions and delivered on the immense talent he has always possessed, 2019 would go down in history as the year he ascended to a celestial realm where mortals do not operate: the realm of African Giants.

Wale Oloworekende

1 Comments

Add your own hot takes